A Problem With the Pledge

“I pledge allegiance to the flag of the United States of America, and to the republic for which it stands, one nation under God, indivisible, with liberty and justice for all.”

March 25, 2019

Every morning, millions of students across the United States stop working, stand up, and pledge their allegiance to the stars and stripes of the American flag. This is a procedure quite familiar to anybody who has ever been in public education, like me. It has had solid consistency throughout my life. However, as I grew older, I found myself less and less attached to the practice.

In elementary school, I would stand and recite the pledge because it was what I was told to do. I did not analyze the words, nor did I care to. I was far too young to do so. When I eventually reached middle school, I had a change of heart. In my ‘tween-age years, I began to develop opinions on national issues and a stronger connection to my country. I stood proud while I pledged my allegiance to my flag despite the many who ignored it out of a lack of energy or interest.

It wasn’t until high school that I began to really listen to the words I was saying. Once I did, I started to question the practices that had been forced before I was matured enough to recognize what was happening. I realized that I had been expected to pledge everlasting, unconditional allegiance to the government and ideals of my country while I was only five years old. I quickly became very suspicious. What was I really agreeing to? Who was expecting me to remain allegiance? Where did this pledge come from anyway? Why did it still exist?

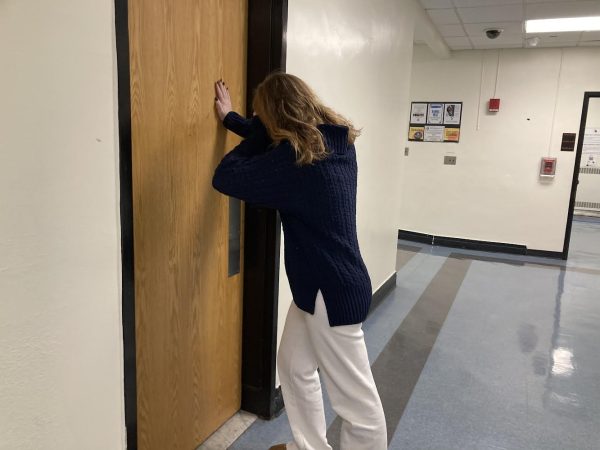

My freshman year of high school, I found myself joining those who stood when asked to stand, but did not actually recite the prose. Now, only two years later, I don’t even blink when the pledge comes on. I continue with whatever I am doing, ignoring those around me who stand to face their flag with their right hand covering their heart and preach some nonsense that they could not care less about. However, there was a very important step in between my freshman year routine and now. One day during my second year of high school, I decided to start saying the pledge again, but I purposefully left out one important phrase: “under god.”

It may have started as an act of simple teenage rebellion, but as months went on, I became more committed to my decision. I became increasingly confused, concerned, and appalled by the national expectation of me to pledge my allegiance to a god every single morning while in public school. I had finally realized that every single morning that I came to school for the past decade, I had been told to stand and put my hand over my heart in what now had felt like a pledge to god. The pledge may not be directly for a god, but it is self-defined as a pledge for a nation that stands only under god.

As someone who does not practice a belief in god, this seems like a far step out of bounds made by the federal government. This nation was formed under the idea that every American citizen would be granted the freedom of religion. The first amendment in the bill of rights in the U.S. Constitution, the very foundation of the American government, includes the words:

“Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof…”

In my interpretation, as well as that of founding father and original inspiration of the ‘separation of church and state’ ideal, Thomas Jefferson, this amendment prohibits the federal government from passing any law that establishes a national religion or prevents, in any way, anybody from practicing their religion freely.

In the U.S. Code, the official, federal compilation of all laws currently in force, both of general and permanent nature, under section four of chapter one of title four, the exact words of the pledge as it is intended to be recited, as well as the proper etiquette of one when stating or listening to the pledge, are written. In June of 1954, the two words “under” and “god” were added to this clause by a law passed through Congress and signed by President Eisenhower. It was believed at the time by most of the government, as seen in many national changes made at the time that the separation of church and state was not really as it is typically interpreted now, but rather that one should not depend on the other.

This was exemplified in the supreme court verdict of the Zorach v. Clauson case which allowed students to be excused from school due to religious observances and education. I understand the decision as it was originally intended by the court because it came from Justice William Douglass, a very religious man. Before the twenty-first century, this debate on church and state was really only about the separation of the Christian church and the federal government, not religion altogether. It was a common claim made by supporters of the addition of “under god” to the pledge that it simply refers to ‘a’ god, not anyone specific god, apparently disparaging any claims that it was associated to “an establishment of religion.”

I can agree with this. I believe that, to date, the federal government as a whole has not attempted to establish a national religion. However, this is not what I am really concerned about with the pledge. I believe that the government absolutely looks down upon those who do not believe in a god. Sure, it is fair to say that someone who follows any monotheistic, or possibly polytheistic, religion can interpret the words “under god” as a reference to their personal god. Yet it is also fair to say that there may be a student in the room who practices atheism, meaning they do not believe in any god. These students may feel ostracized by the federal order to make a pledge daily to what they perceive to be a fictional being.

Atheism is a religious belief system in its own right. The passing of a law that involves god into any federal practice, let alone a practice that is forced upon children far too young to develop their own religious conclusions, definitely prohibits the free exercise of religion in America. In this evolving and liberalizing modern world, atheism, and many other ideas that lessen the importance of religious values, have gained traction in the nation’s population. About three percent of the population (over ten million people) claim to be atheists, and as the age ranges get younger, this percentage increases.

A large part of the nation is being ignored and refused one of their natural rights as a U.S. citizen every single morning that the 50 million American children pledge to a nation “under god.” It is about time for a change in this nation, one that separates the state from religion with complete liberty and justice for all—one that returns to pledge of allegiance to its secular form.

Lynn • Aug 19, 2020 at 8:45 pm

Yes, and now you can see what happens to society without it.

Michael Scott • Mar 26, 2019 at 4:54 pm

It’s an interesting take on those two word of the pledge, but it’s all about how you interpret it. The ‘under god’ can just mean America is the most powerful, great, and moral entity next to a god should one exists. I mean I don’t believe in god either but it serves no purpose and does not do anything to get worked up about those words. But I would also like to add that the pledge is statement of our loyalty to America and it’s not mindless. America was founded on many principles such as capitalism, free speech, right to bear arms, etc. these are the principles people agree to uphold when stating the pledge. Nice try kid.

Andrew Patashnik • Mar 28, 2019 at 1:02 pm

Hello! Thank you for reading my piece and for the comment. I completely understand the fundamentals behind the pledge and the respect it deserves, so I would not try to fight its existence at this point. My main qualm is the inclusion of “god” in the practice, not the practice itself. I believe that if children are to be exposed to religion, it should not be through their public school but through their families. As for your other points, I believe that it is actually worth it to fight against this, as I believe that there are many harmful effects that religion can have on society, especially when it is involved in the government, which public education is. The pledge is important, as you say, and not mindless, but students mindlessLY state it. I am concerned with students mindlessLY pledging their allegiance to a nation UNDER god without really thinking about it. That is all. Again, this is just my opinion and I acknowledge and respect those who disagree. Thank you for getting involved and replying!

Lorraine Grasso • Mar 26, 2019 at 9:34 am

Hear! Hear! Well written piece, Andrew. I have been confounded by this pledge since I first came to this country. in Ireland, we had to say a prayer in the morning before class but that was a Catholic school so it sort of made sense. The fact that there is supposed to be a separation of church and state flies directly in the face of “the pledge”. Great article!