Reading Without Seeing: A Closer Look At Braille

February 23, 2015

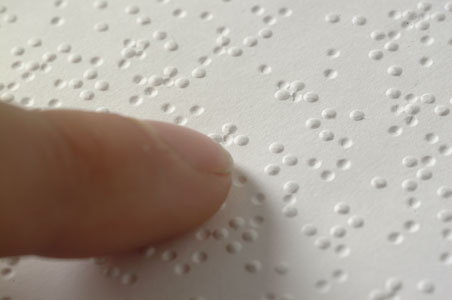

You may have noticed it on the classroom number signs around school, or maybe you’ve seen it on the signs for public restrooms or elevators: a series of little raised bumps underneath the written words. They can be found in a lot of places, but what is the significance of these dots? They’re cool to touch and run your fingers over, but do they really mean anything?

Actually, yes, they do, and they’re really very important to some people.

Collectively, those raised bumps are known as Braille, a reading system used by the blind. They might not be relevant in your personal life, but there’s a whole community of people that rely on those funny-looking dots to be independent, productive members of society.

Originally, this method of raising dots in paper was used by military personnel. They imprinted the bumps in order to pass secret messages to one another that could not be decoded by anyone else. These bumps were also designed to be read by touch, so they could be read while hiding in the dark.

A young man named Louis Braille adapted the simple code and transformed it into a complex, sophisticated way of communicating written language. The original system was too basic for literary use, as it only covered symbols for short messages and phrases, like, “Enemy on left.” Braille took the same principles and applied it to everyday language. Now, 200 years later, the almost unchanged system is used by the blind to access anything that a sighted person could read visually.

Though it might not seem difficult at first, Braille is a rather complicated code that takes most people years to learn and master. It consists of different shorthand symbols that represent different letters or words. In a nutshell, it works like this:

Each Braille cell is made up by a maximum of six raised dots. Anywhere between one and all six of these dots are arranged uniquely to make a certain character that conveys a certain meaning.

Still following along? Here’s where it really gets hard: because there are only six different dots, only so many patterns can be made. Therefore, a character often has more than one meaning, depending on its position relative to the other dots in the cell, location in a sentence, and surrounding characters. For example, the character that represents the letter “h” can also be the word “have” when used independently of any other character, the word “his” when positioned on the lower dots of the six-dot cell, an open quotation mark at the beginning of a sentence, or a question mark, when it is at the end of a sentence. And, of course, it can be used as a regular “h.” Though these are the only characters represented by the “h,” other symbols can also stand for parts of words or groups of letters, in addition to whole words and punctuation.

In order to perfect Braille skills, and use them both accurately and efficiently, a person must learn (that is, memorize) all these different characters, the various meanings they can have, and the even more numerous amount of rules that accompany each one. These shorthand codes for groups of letters and whole words are called contractions, and there are about 167 of them. Add to that the three or four meanings each one has that must be memorized, along with the two or three rules that coincide with every cluster of a few contractions, and yeah, there is a lot to be remembered.

Okay, so we have the meaning down. But how do you even make those dots? Back in the day, braille readers used a slate, a small template with depressions, and a stylus, a writing tool that is used to press the paper into the depressions of the slate. Brailling with a slate and stylus is hard, tedious work, as it is easy to confuse the positions of the dots within the cell. All characters are entered in the reverse image so that when the paper is flipped over to the side with the raised dots, the cell is oriented correctly. It is much easier to use a “brailler,” a heavy device, similar in size, shape, and form to a typewriter, with six keys that match up with the six dots in a character. Special paper is loaded into it, “brailled on,” and rolled back out, ready to be read.

Though learning Braille is hard work that requires time, dedication, and practice, the benefits of Braille for a blind person are so tremendous that it makes all the effort worth it. Stanley St. Rose, a visually impaired student at Stamford High School who is a fluent Braille-reader, says, “Learning how to read Braille has enabled me to be the best that I can be on the educational level without using my vision.”

Of course, aside from the all-important educational purposes, there are other cool perks to being able to read a code that most others can’t. “Braille is almost like my own private language,” St. Rose added. “It’s always funny to see visual readers try to read Braille.”

Mr. Katz • Feb 28, 2015 at 11:04 am

Interesting! I didn’t realize it was so complicated. It’s been a pleasure to see your and Stanley’s memory ability and dedication in mathematics. I am continually inspired.

Well done!