More Power to the Students

Should students be able to grade their teachers?

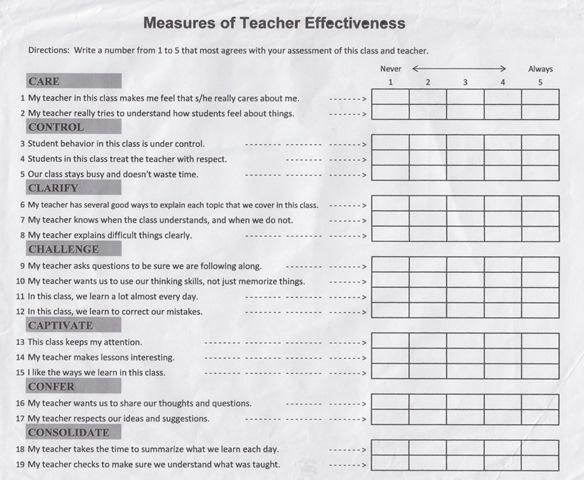

An abridged mock-up of a student evaluation survey based on Panorama Education

October 24, 2014

A technological start-up company called Panorama Education has recently swept the nation, focusing on one simple concept: student evaluation of teachers. To many of us, such a concept is quite alien… but should it be? In an ideal world, teachers can learn from their students as much as students learn from their teachers. And the principle itself is sound: who better to assess teachers than those who witness and are subject to their methods firsthand? That is the basic theory behind Panorama, this according to Aaron Feuer, co-founder and chief executive of the company. “Five years ago we thought test scores were the answer to everything,” Feuer states. “We’re offering a way to focus on the right metrics.” Feuer’s so-called “right metrics” have been tested in over 5,000 schools across the country and have been adopted by some of the largest school districts in the country, including the Los Angeles Unified School district, with overwhelmingly positive results. So the question becomes: Should this be implemented at Stamford High School?

The faculty seems to think so – at least to a certain degree. “Of course I want to know if my kids think I’m doing a good job,” said English teacher Melissa Hadsell. “Who wouldn’t?” The answer: nearly everyone. Although nine out of ten teachers confirmed that they see value in student assessment of some form, the same teachers were shown an abridged mock-up survey based on the Panorama Education model (shown above); here, some doubt began to arise. While some, like foreign language teacher Maria Cahill, had no complaints – calling the scale “incredibly comprehensive,” others were skeptical. “Something more qualitative would be more beneficial,” said history teacher Matt Moynihan. Science teacher Tara Karlson weighed in as well, adding “I’d rather have an environment where students feel they can come to me, personally, and tell me what I’m doing wrong…or even what I’m doing right.” Despite minor misgivings from some parties, nine out of ten teachers once again said they would employ the system, in their classroom, if given the option.

These numbers dropped severely, however, when teachers were asked if they would allow the student assessment to be a part of their overall evaluation. Only three of the ten said they would be comfortable with this. Many who said they would not be comfortable with such a method feared that, if it were employed, quality teaching would take a backseat to popularity. “Kids have a skewed vision of teachers based on how much they like them,” stated physical education teacher Michael Nazzaro. Moynihan added, “Some of the best teachers are demanding – students are often angered by that.” History teacher Michael Brown was a part of the minority opinion, stating that he “wouldn’t mind using this as a small factor,” but that a teacher “shouldn’t get fired solely based on this scale.”

So in the end, the question is really not a matter of whether student assessments should be implemented and/or valued, but to what extent? As we move toward a new era of education in the coming years, represented by companies such as Panorama Education, Stamford High will have to figure out whether it wants to change with the times or keep with tradition. The fact that only 30% of teachers surveyed would put their jobs on the line in order to give students more of a say, shows that advance in this direction may be quite the challenge. As science teacher Kristen Amon bluntly stated, “Teenagers are highly unreliable.” Based on the data, it is difficult to say that she does not hold the prevailing opinion.